A friend asked me yesterday what we do with our time now that we live on the boat. I came up with a list of things, awkwardly put together and here expanded:

- (In summer) Priority 1, find shade or a clean-ish place to swim

- Check the anchor

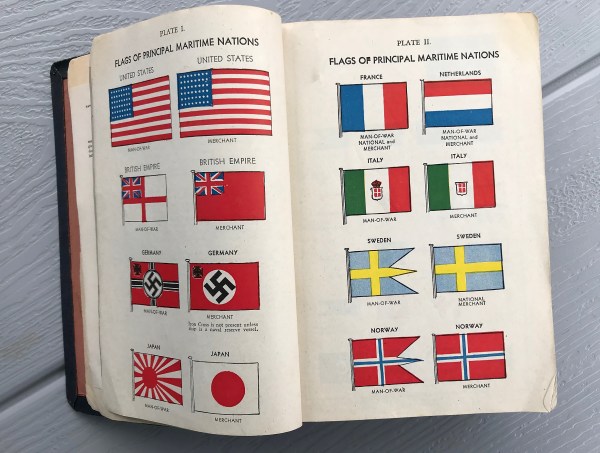

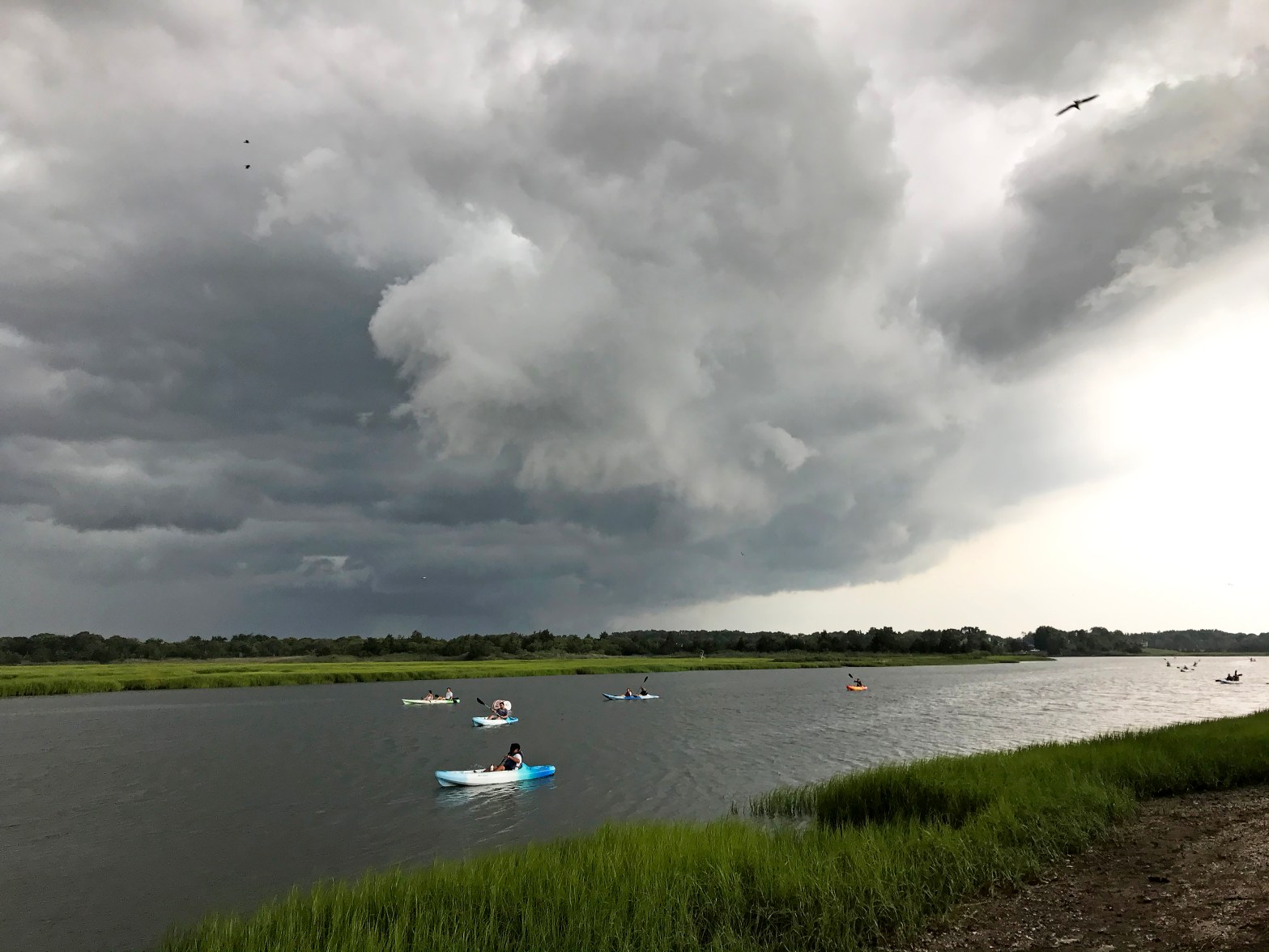

- Check the weather

- Find and fix broken things on boat

- Learn the things we need to know and don’t yet, like how to fix broken things on the boat

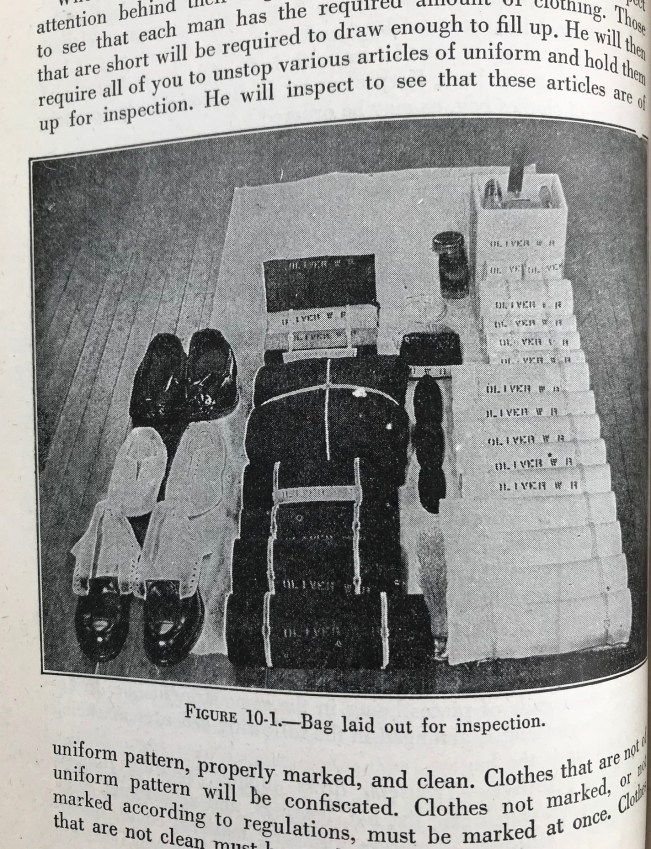

- Organize/reorganize

- Clean boat

- (If raining) Clean ourselves

- Feed ourselves

- Explore

- Check the weather

- Check the anchor

- Write

- Read

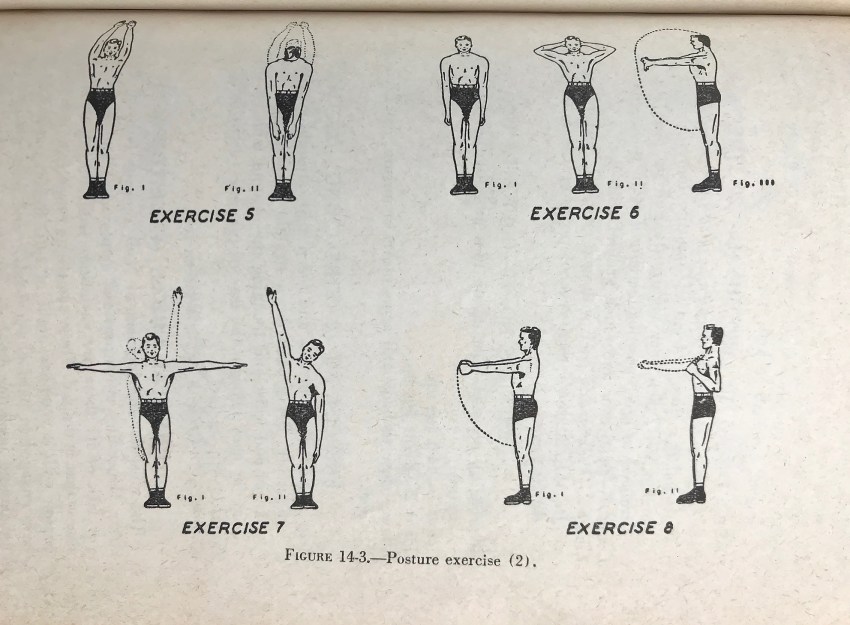

- Stretch, meditate

- Check the weather

- Go to bed

- Remember to turn on the anchor light

- Check the anchor

- Go back to bed.

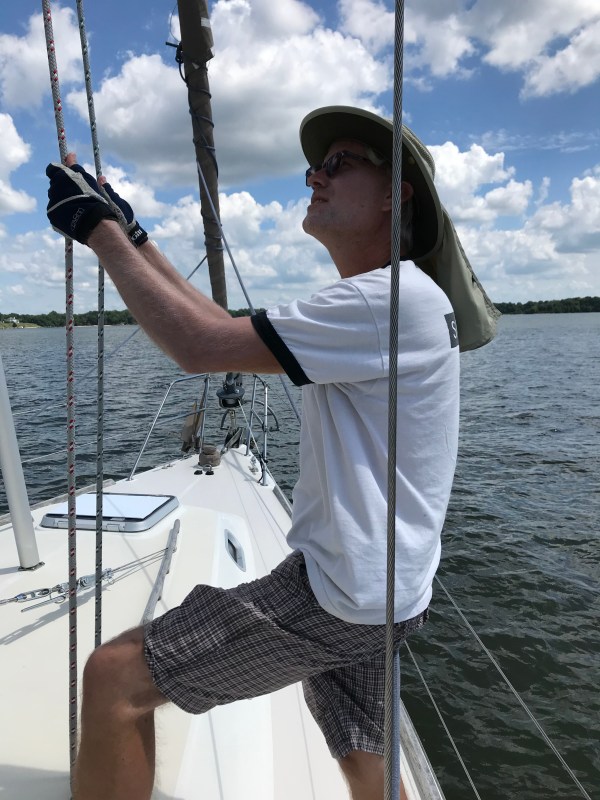

Oh and also sailing.

Prior to moving onto the boat I had all sorts of ideas for what I was going to do with the immense amount of time I would have on my hands and the tremendous peace of mind I would find being away from work that daily tore me up inside, leaving me so mentally and emotionally exhausted by the end of the day that all I could manage was a few hours of television before laying awake fighting insomnia.

Time gets filled.

There is always something to worry about.

I realized pretty quickly that time would be liberally spent doing things I didn’t need to do when living on land (trying to escape oppressive heat, making sure my home wasn’t floating away toward some shoal or other boat, keeping a constant eye on the weather) or doing things that now take three times as long as they did on land (everything). But, something big has nonetheless shifted. Anxieties are real, related to the well-being of the boat, Bill or myself, in the right now, and these worries must be managed, but they are also manageable in a way that climate change and wildlife extinction are not. Also, I find that when I do have an hour or so free I don’t have to spend as much of it decompressing from nebulous anxiety and can instead spend it diving deep into a single Mary Oliver poem, or jotting down notes for a fiction book, or reading, reading, reading. I’ve read more in the past 5 months than I did in the 5 years leading up to this trip. And this week’s blog is a recap/review of what I’ve read.

First come the books I have already finished. I have limited physical books, because space is so tight, a kindle with many dozens of books, and a good list of audiobooks.

I generally read physical books during daylight hours and listen to audiobooks when I want to fall asleep–it helps to shut out boat noises so I don’t lay awake worrying that each new click or rattle is telling me the boat is sinking.

I’ve enjoyed each of these books in some way… some more than others.

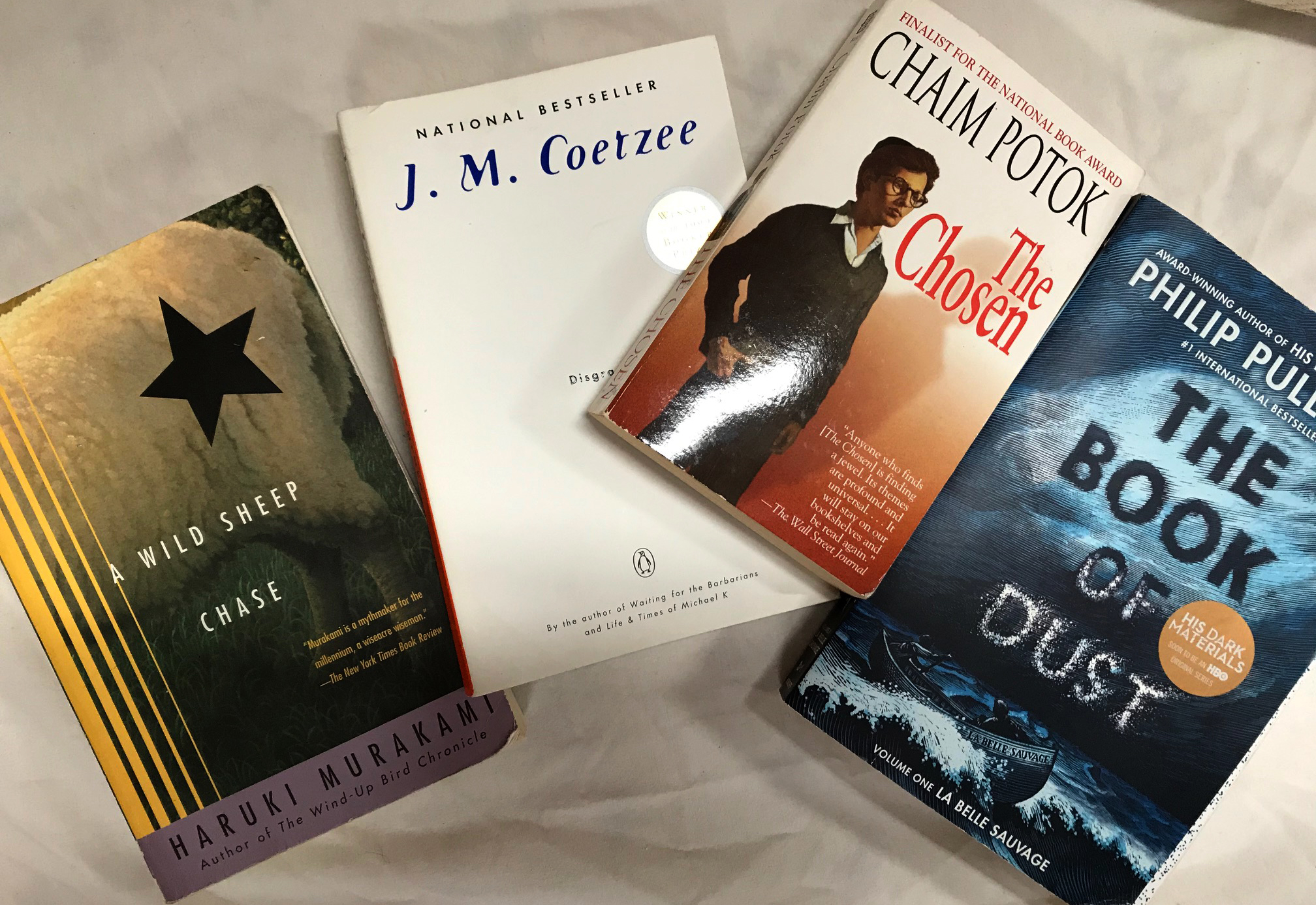

- A Wild Sheep Chase, Haruki Murakami. Here we have a zany book, part mythology, part slacker comedy. I highly recommend it if you want some light but smart reading from an incredible author.

- Disgrace, J.M. Coetzee. The main character in this book is a creep in the beginning of the book, a creep in the middle, and a creep at the end (spoiler alert). As a reader, there’s something difficult about that, but Coetzee is such a deft writer that the story of this creep’s minor enlightenments is enough to make this book charge forward and stay with you. I continue to ponder the meaning of the word disgrace and conversely the meaning of the word grace, long after closing this book and passing it on to Bill. I recommend Coetzee’s Disgrace for sure, but this is not light reading.

- Lord of the Rings trilogy, J.R.R Tolkien. This should really be first on any list of books for me. I have read it perhaps a dozen times in my life, listened to the audiobooks almost as many times, and seen every LOTR movie ever made more than a few times. Of any single work of story, I have devoted more of my life to Tolkien, than any other creator. And I will never tire of this story or the way Tolkien has told it. Flawless? No, some of the language is stuck hard in the gooey amber of time. But I have read and loved a lot of fantasy books and for me none even comes close to the sincere genius of the LOTR.

- The Witcher series, Andrzej Sapkowski. This is one of those good fantasy series that doesn’t measure up to Tolkien, but I still really like it! I’m listening on Audible to this series. It has elves, dwarves, even halflings, and some interesting conflicts that reflect modern political times.

- The Chosen, Chaim Potok. I read this book in college and just re-read it on the boat. It’s amazing how a few decades changes your perspective on a story. I still love it as a great coming of age story set in the Jewish community of New York City, post World War 2. But there are plot complications I didn’t understand back then, such as the violence that sprang from the formation of the nation of Israel. It is hard to read this book the same way having seen how the world unfolded since it was written in the late 1980s. Still, I recommend it. It is a story well told and gives such an interesting insight into the diversity of the Jewish community/culture.

- The Book of Dust/La Belle Sauvage, Philip Pullman. This book is a prequel to the Golden Compass series. I don’t think I like it quite as well as the older series of Lyra’s adventures in a twisted world where adults are experimenting on children to see if they can rid the world of Original Sin (a story both unsettlingly familiar and fascinatingly foreign). But I’m a big fan of Pullman and the book fills in some history of Lyra’s story while also telling the story of a plucky young boy with a magical little boat La Belle Sauvage. Pullman recently released another book called The Secret Commonwealth that picks up the story after the events of The Golden Compass. I’m eager to read this one after I re-read the original book series.

- American Gods, Neil Gaiman. I listened to a great audio version of this book. So goooood. I’m not sure I could say what it is about. A guy, a bunch of gods nobody believes in anymore going to war with the new gods of technology and commerce. Heady and ridiculous at the same time.

- The Cuckoo’s Calling, Robert Galbraith (aka J.K. Rowling). This was another audiobook, not a great choice for listening to at night, too suspenseful to get me sleepy. But if you like mysteries this is a good one and the audiobook is very well done.

- The No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency, Alexander McCall Smith. This is a sweet novel about a woman in Botswana who opens a detective agency. The audiobook is excellent, the story both light and heavy and full of charm. Makes me hope that the Maggie May makes it to Africa someday.

- The Mists of Avalon series, Marion Zimmer Bradley. I am not the biggest fan of this series, but I got sucked in! It is a story of the Arthurian legend but told more from the perspective of the female characters. Zimmer Bradley offers an interesting take on the legend, but some of the things these characters do and say…questionable. Still, it’s light and pretty entertaining and takes a known legend to a different place. And I’m listening to the audiobook, which puts me to sleep nicely.

- The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller. Another excellent audiobook. This book is by the same author as the well-known Circe, and both are fresh reimaginings of characters from Greek mythology. Miller has a clear talent with retellings like this, and Achilles explores the relationship between a Greek demigod and his closest friend/lover Patroclus. Like Circe, Mists of Avalon, and well, most of the books on this list, The Song of Achilles is at its foundations entertainment. But it is also such a well-told love story between two men that it offers a profundity that sneaks up on you. The audiobook is very well done.

Current Reading

My current list includes all of the above titles, as well as a book on tides, and I’m loving them all for different reasons. I am less than halfway through The Writer’s Map, but can already say I highly recommend it. It’s a collection of fictional maps and essays by writers who rely heavily on maps, or who were inspired by other author’s maps. Visually it is fathomless. Each map contains an entire world, from which sprung some of the most inventive stories throughout human recorded history. I am rapt. I read this book in the mornings, after writing in my journal, while drinking coffee, before writing in my fiction journal. I love it so much. And it is a book I never would have picked up over the past 20 years, just because I didn’t have time to let my imagination wander through its pages.

Modern Marine Weather by David Burch is a different animal altogether. This is a book I read for survival. So that when we, s’cuse me, if we get to a place where we don’t have easy access to communications, I can assess what to expect from wind and waves just by looking at a spare surface chart, the barometer, clouds, wind directions and shifts, and sea state. I need to read this book three times to get to the point where I am competent. I’m about halfway through my first reading.

Myths and Legends is basically an illustrated encyclopedia of mythological characters worldwide. I use it as a reference and hope to make it to some of the countries whose myths are contained in the book.

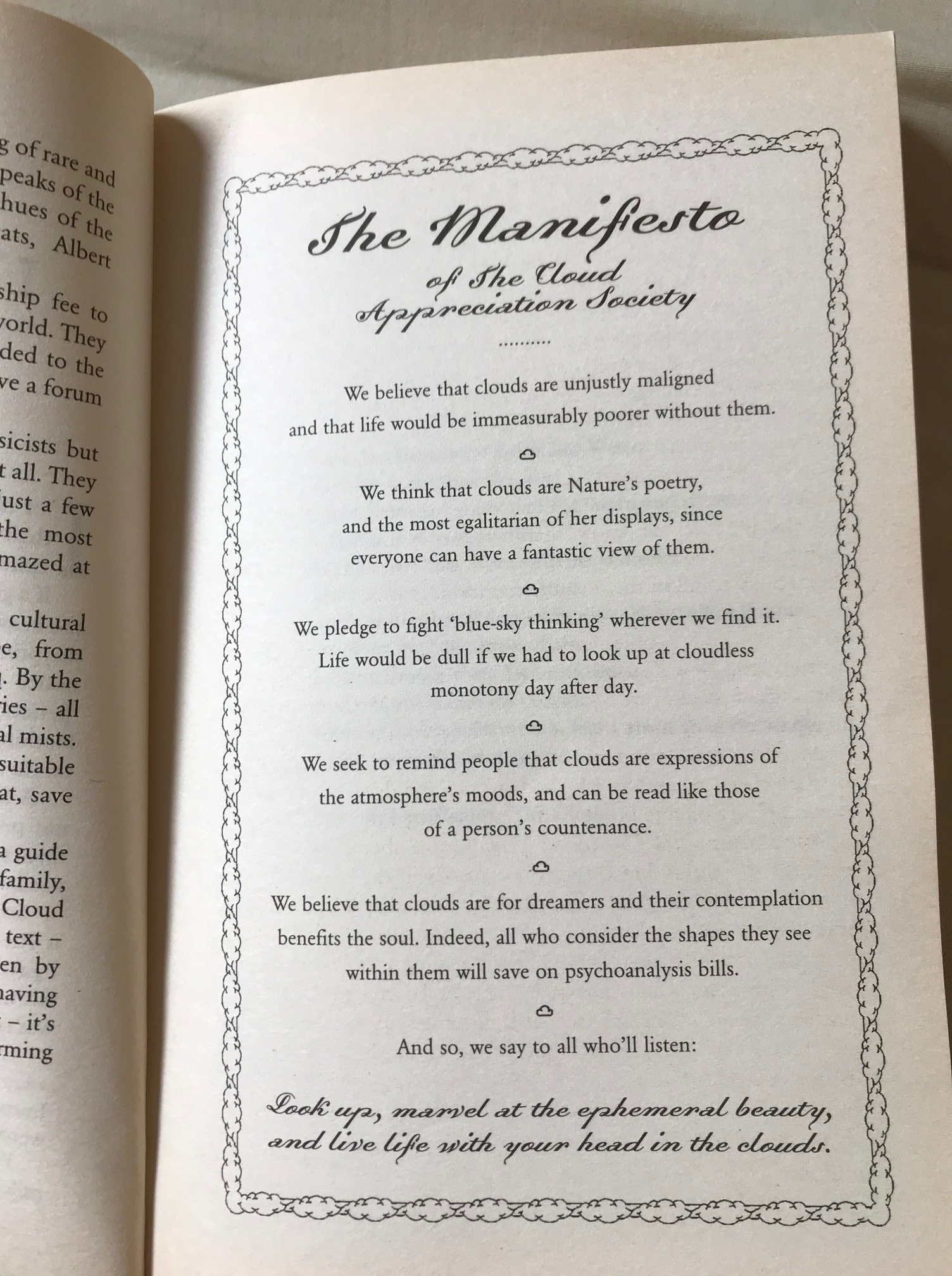

Last, but certainly not least is The Cloudspotter’s Guide. My friend Edward gave me this book last week to my delight. Last time Bill and I saw him, right after we moved aboard the boat, Edward was telling us about how he had joined the Cloud Appreciation Society and was reading a book by its founder Gavin Pretor-Pinney, who also wrote a Manifesto about appreciating clouds. Every morning the first thing I do upon waking is to read this book. Every evening Bill and I watch the sunset and practice appreciating clouds, so that one day we may join the society with our heads held high. I love this book. It is, depending on the page, a nutty examination of the history of cloud pornography, a declaration of the oppressive nature of blue-sky thinking, and a serious explanation of the classification and formation of clouds.

Thanks to all who have gifted me books. They guide my life and thinking aboard the boat, help me sleep at night, and shower me with profound riches. Many days this is the only shower I get.

If you have any book recommendations, or comments on the books herein, please leave comments.

Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland…all places I wasn’t expecting or hoping to to blog about at the end of June 2020, but that is the way of adventures.

Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland…all places I wasn’t expecting or hoping to to blog about at the end of June 2020, but that is the way of adventures.

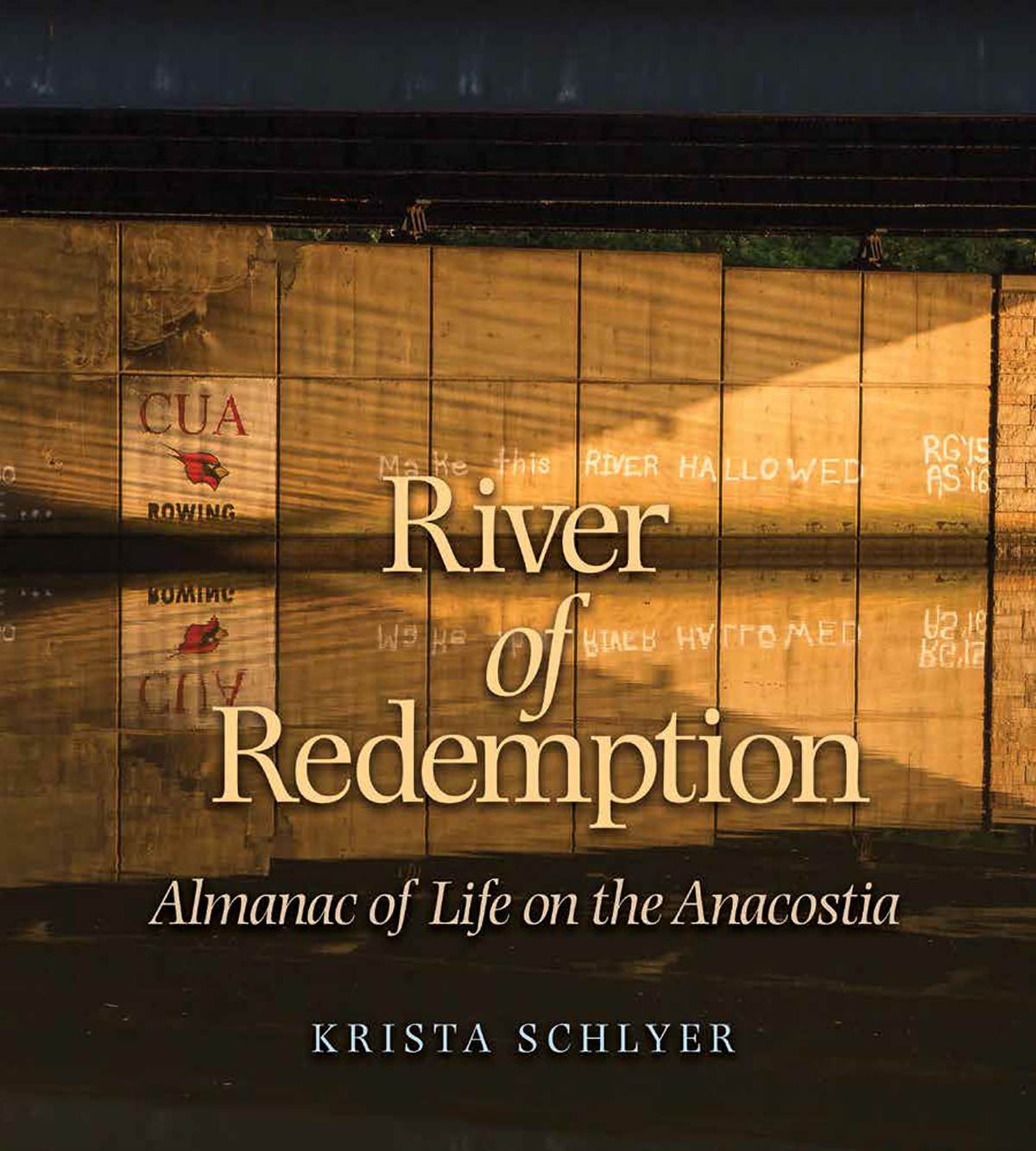

At the Arboretum, I look for a conduit to an ecological synapse that has not been fully severed, hoping to conjure the lush land that sprouted as the Pleistocene chill abated, a land that felt the feet of badgers, bison, and wolves, that met the eyes of the first humans who ever set foot here in the Anacostia watershed. It is nothing more than an intellectual exercise–that watershed is gone forever. But the practice offers something important. Here at this spot in the Arboretum, called the Fern Valley Trail, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has endeavored to recreate a piece of that native Anacostia in the upland woods, the forest floor, the bend of a clear creek rushing down the hillside toward the river. There is no place like it in the Anacostia watershed for the density of land remembrance.

At the Arboretum, I look for a conduit to an ecological synapse that has not been fully severed, hoping to conjure the lush land that sprouted as the Pleistocene chill abated, a land that felt the feet of badgers, bison, and wolves, that met the eyes of the first humans who ever set foot here in the Anacostia watershed. It is nothing more than an intellectual exercise–that watershed is gone forever. But the practice offers something important. Here at this spot in the Arboretum, called the Fern Valley Trail, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has endeavored to recreate a piece of that native Anacostia in the upland woods, the forest floor, the bend of a clear creek rushing down the hillside toward the river. There is no place like it in the Anacostia watershed for the density of land remembrance.

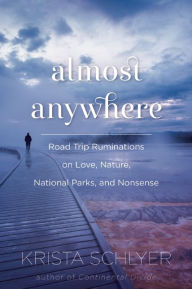

Although at times it is funny, that’s true (one reviewer called it a cross between Wild and Let’s Pretend This Never Happened). But Schlyer writes about her husband who (spoiler alert) died, so hers is a story about grief, too.

Although at times it is funny, that’s true (one reviewer called it a cross between Wild and Let’s Pretend This Never Happened). But Schlyer writes about her husband who (spoiler alert) died, so hers is a story about grief, too.