Wednesday morning at dawn a solitary pied-billed grebe paddled through a misty oxbow lake called La Parida Banco in the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge. La Parida translates from Spanish as: one who has just given birth, perhaps the most apt description I’ve ever heard for a wildlife refuge. I contemplated this meaningContinue reading “La Parida: Where the Wild Things Were”

Tag Archives: border

Border Angels vs Excavators

Like many South Texas mornings, yesterday’s dawn was sung into existence by Altamira orioles, great kiskadees and green jays, warblers and cardinals. It’s hard to imagine any hurt could go unhealed in a world where the birds chorus at dawn. So it seemed for a brief eternity as I walked west through the northern edgeContinue reading “Border Angels vs Excavators”

Border Wall Construction Begins, again

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. I can still hear Americans cheering when Ronald Regan demanded “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Today is also the 10th anniversary of a much lesser known historical event — the Borderlands RAVE. It was an expedition I organized with the InternationalContinue reading “Border Wall Construction Begins, again”

Ay Santa Ana

Santa Ana and the battle for sacred ground There are some places in this world where life and beauty effervesce from the ground itself, places we simply can not lose. There are landscapes where lines must be drawn in the proverbial sand and we must say, no, you will not take this from the world.Continue reading “Ay Santa Ana”

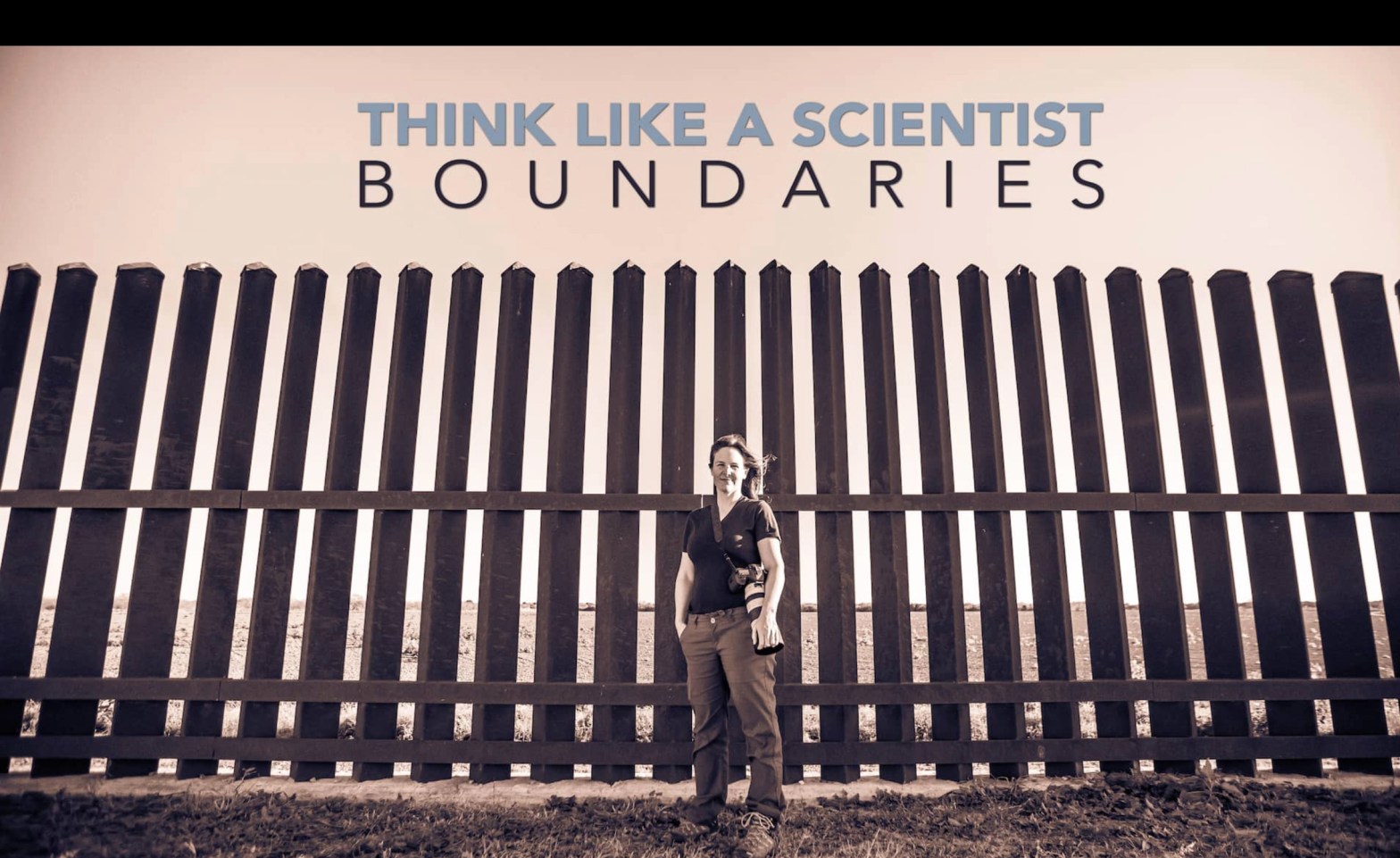

New Film: Border Walls and Boundaries

The US-Mexico border wall boondoggle didn’t start with Donald Trump. Despite its exorbitant cost, wasteful, ineffective nature, and destructive impact, all of the current presidential hopefuls – on both sides of the political spectrum – have voted in support of border wall on the southern US border. Bernie in 2013, Hillary in 2006, Ted CruzContinue reading “New Film: Border Walls and Boundaries”

A Cry for the Borderlands Into the Partisan Wilderness of Washington DC

For 10 years, ever since the passage of the REAL ID Act in 2005, the wildlife, people and ecosystems of the US-Mexico borderlands have suffered the destruction of unprecedented militarization and the waiver of environmental and many other laws. Senator John McCain is working to expand borderlands destruction and disenfranchisement through a bill S750, cynicallyContinue reading “A Cry for the Borderlands Into the Partisan Wilderness of Washington DC”

The Pity of Donald Trump

As I watched Donald Trump repeat his “more border wall” mantra last night during the first GOP primary debate, my mind returned to a moment earlier in the day when I was working on an annual report for Humane Borders, a non-profit dedicated to providing humanitarian aid to vulnerable migrants traveling the arid Arizona borderlands.Continue reading “The Pity of Donald Trump”

Borderlands book wins National Outdoor Book Award

My book about the US-Mexico borderlands was honored with a National Outdoor Book Award for 2013. The book is available on my website, Amazon, and many bookstores nationwide.