I woke this morning at first light and climbed the four steep companionway stairs into the cockpit. I have climbed these stairs 1000 times in the past 18 months. The boat interior was dark but the sun, still below the mountains to the east, cast a pale light on the clouds in the western sky.Continue reading “The Beginning”

Tag Archives: book

The Wealth of Time

A friend asked me yesterday what we do with our time now that we live on the boat. I came up with a list of things, awkwardly put together and here expanded: (In summer) Priority 1, find shade or a clean-ish place to swim Check the anchor Check the weather Find and fix broken thingsContinue reading “The Wealth of Time”

Confluence Moon

The following text is excerpted from River of Redemption: Almanac of Life on the Anacostia, published in November 2018 by Texas A&M University Press. Each chapter of the book is titled according to the custom of many native North American cultures, to name a month for the defining quality of its days. Anacostia Almanac months areContinue reading “Confluence Moon”

Waking Moon

The following text is excerpted from River of Redemption: Almanac of Life on the Anacostia, published in November 2018 by Texas A&M University Press. Each chapter of the book is titled according to the custom of many native North American cultures, to name a month for the defining quality of its days. Anacostia Almanac months areContinue reading “Waking Moon”

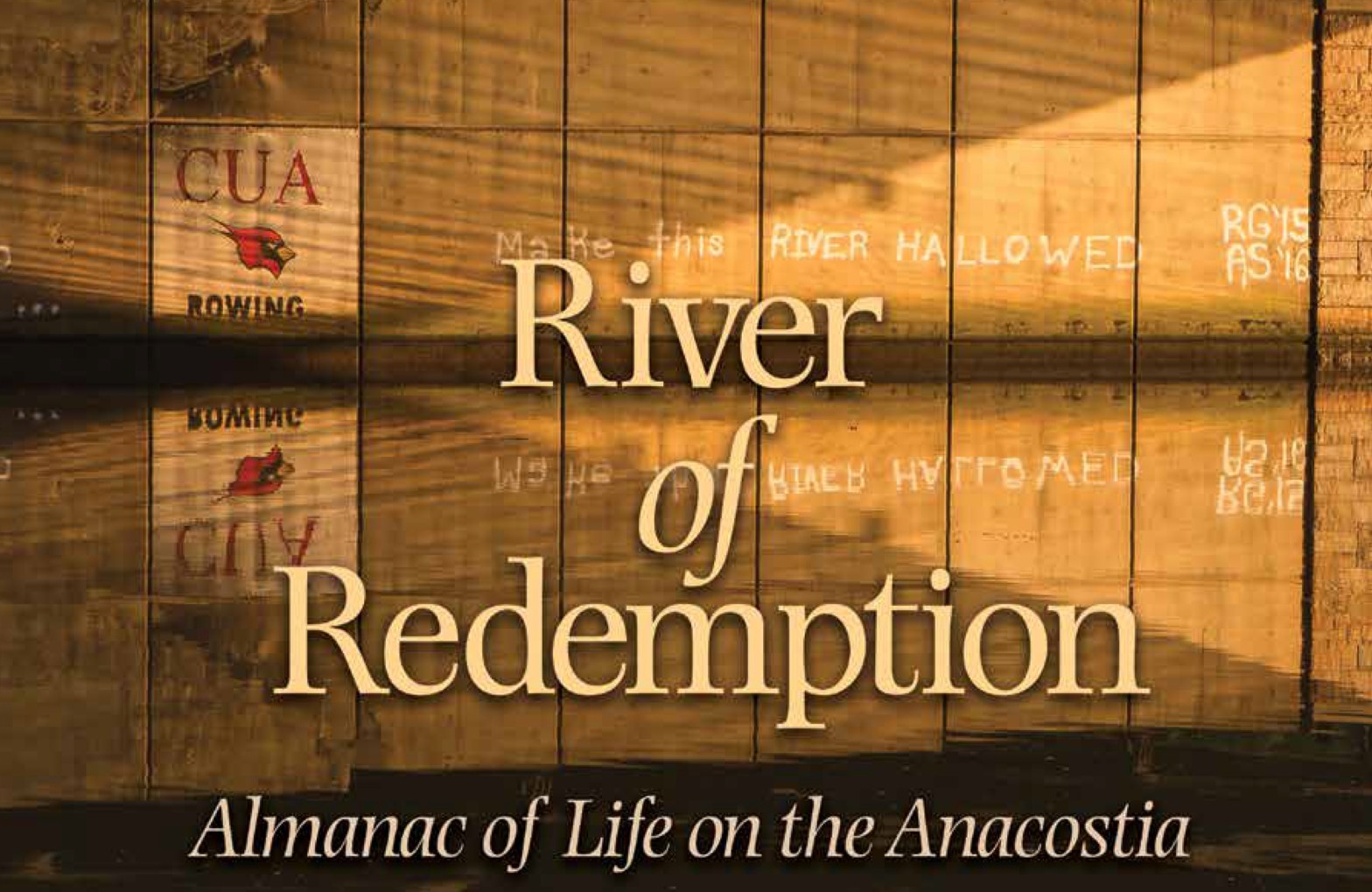

River of Redemption: Almanac of Life on the Anacostia

Incorporating seven years of photography and research, River of Redemption portrays life along the Anacostia River, a Washington, DC, waterway rich in history and biodiversity that nonetheless lingered for years in obscurity and neglect in our nation’s capital.

Inspired by Aldo Leopold’s classic book, A Sand County Almanac, Krista Schlyer evokes a consciousness of time and place, inviting readers to experience the seasons of the Anacostia year, along with the waxing and waning of river’s complex cultural and ecological history.

Blending photography with informative and poignant text, River of Redemption urges readers to seize the opportunity to reinvent our role in urban ecology and to redeem our relationship with this national river and watersheds nationwide.

Memoir about journey through nature inspires

Originally posted on Monica Lee:

The only I didn’t really like about Krista Schlyer’s memoir was the title, Almost Anywhere: Road Trip Ruminations on Love, Nature, National Parks, and Nonsense, because that makes it sound vague and light-hearted. And it’s really not. Although at times it is funny, that’s true (one reviewer called it a…

Almost Anywhere in Denver

I’m coming to Denver! I’ll be doing a book reading and signing for Almost Anywhere: Road Trip Ruminations on Love, Nature, National Parks and Nonsense at the Tattered Cover on December 10. In a nutshell the book tells the story of a trio of misfits wandering the American road in search of wild nature, national parksContinue reading “Almost Anywhere in Denver”

The Sinlessness of Predation

This week I’m starting a monthly blog of excerpts from my new book Almost Anywhere: Road Trip Ruminations on Love, Nature, National Parks and Nonsense. This first excerpt is one of my favorite passages from the book, about one of my favorite places, the Cranberry Glades Botanical Area in the Monongahela National Forest of WestContinue reading “The Sinlessness of Predation”

My new book – Almost Anywhere – released today!

My new book, Almost Anywhere: Road Trip Ruminations on Love, Nature, National Parks and Nonsense, has been released today by Skyhorse Publishing. Win a copy of the book on Goodreads! The book tells the story of a year-long adventure I took around the United States to almost every national park and many other wildContinue reading “My new book – Almost Anywhere – released today!”

Almost Anywhere coming soon!

My newest book, Almost Anywhere is scheduled for release October 6 from Skyhorse Publishing. You can pre-order in my website Book Store and in book stores nationwide. Advance reviews for Almost Anywhere: “Outstanding, wry, heart-wrenching and healing. Those words describe Almost Anywhere, which hits the bull’s-eye as a cross between Wild and Let’s Pretend This Never Happened. Krista’s unique voiceContinue reading “Almost Anywhere coming soon!”

Borderlands book wins National Outdoor Book Award

My book about the US-Mexico borderlands was honored with a National Outdoor Book Award for 2013. The book is available on my website, Amazon, and many bookstores nationwide.